A micro adventure into luxury in the midst of savage beauty took us north around Killary Fiord and into Mayo and the lonely Delphi valley. Following the Bundorragh river up from the little harbour on the fiord we passed Fin Lough and swept up the tree lined drive to the serenely cosseted environs of Delphi lodge.

A micro adventure into luxury in the midst of savage beauty took us north around Killary Fiord and into Mayo and the lonely Delphi valley. Following the Bundorragh river up from the little harbour on the fiord we passed Fin Lough and swept up the tree lined drive to the serenely cosseted environs of Delphi lodge.

The 1000 acre estate and Georgian country house , built for the Marquis of Sligo in the 1830’s, is a renowned salmon and sea trout fishery surrounded by the tallest mountains in Connaught. At great pains to point out it is not run as an hotel ( no room service, no tv, no porter, no menu choices etc) it is still very popular with paying guests, many of whom return time and again to fly fish and relax. The dining is communal around a massive oak table and the bar is self service/ honesty book. There’s a billiards room, a library well stocked with shooting and fishing tales and a sofa stuffed lounge where canapés are served pre dinner.

King Charles, or Prince Charles at the time, had stayed in our room for a couple of nights on a solo painting and fishing trip back in 1995, the very first trip by a British royal to the republic since the foundation of the state. I fancied I could smell the privilege around the four poster bed.

With the scudding tumulus creating a light show of sun and shade across the lake and mountains we were drawn out to explore. Following the Owengarr river upstream from Fin Lough towards Doo Lough we marvelled at the clarity of the water. Before too long we reached the hatchery where 50,000 salmon smolts are raised and released a year, dramatically increasing the salmon population. To protect the genetic integrity of the wild fish all those from the hatchery, marked by clipped fins, are killed if caught whereas any wild fish must be released. All sea trout are released. The big circular tanks were writhing with life.

Walking back through the woodland we noticed the invasive rhododendron had been effectively dealt with by cutting slots and presumably poisoning. The Atlantic Rainforest climate made for a mossy green environment in one of Irelands wettest places.

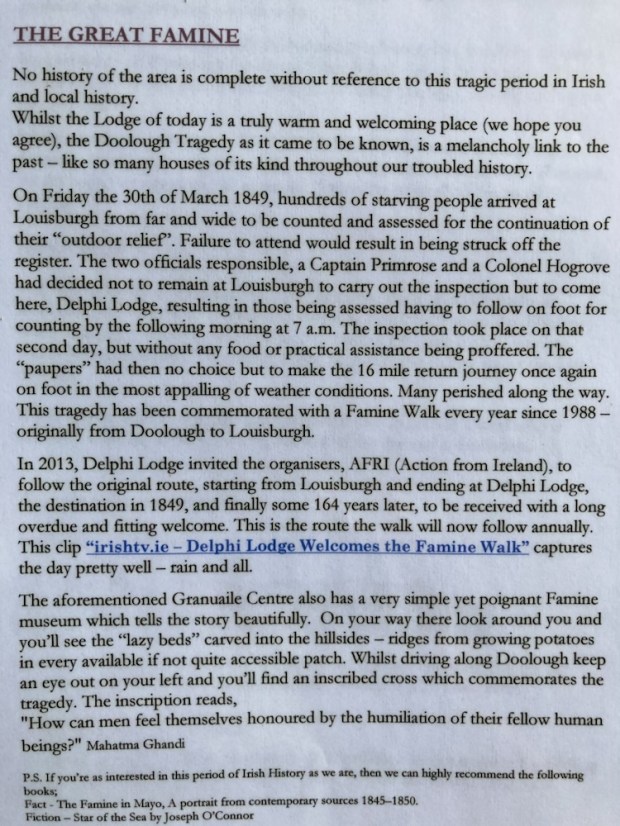

After our night in the room resonating with the memory of a royal we travelled up the road a little to the scene of a famine era tragedy caused by a heartless colonial British Empire.

I’d been on a couple of the Famine Walks from Delphi Lodge to Louisburgh mentioned above and found them a powerful collective experience that focuses on the many injustices that continue around the world. The fine weather removed the gloom that can linger here under a dark and oppressive sky and we took a trip a little way up the Glenummera river that runs into Doo Lough from the Sherry Hills to the east.

Returning to Delphi and saying our goodbyes as the fisherman cast their flys into the lake we moved back south to the head of the fiord to walk the Western Way along the Erriff river.

Starting out from the famous Assleagh Falls, where Sir David Attenborough was filmed explaining the life history of the eel and a fight sequence appeared in the movie of John B Keane’s The Field, we followed the waters upstream.

The country opened up before us, the wide Erriff valley faced with the Devils Mother to the south and Ben Gorm rearing up to the north. The river is one of Ireland’s premier salmon fishing rivers and has been designated as the National Salmonid Index Catchment, used as a prime example of a salmonid river system of high quality with a research station and trapping facilities. Managed by Inland Fisheries Ireland who carry out a wide range of research and monitoring on salmon, sea trout and brown trout, the work involves cooperation with lots of national and international research partners.

We came upon a few fly fisherman trying their luck, testing their skills, but mostly the valley was empty apart from a few sheep, one of whom had an unfortunate problem with a hugely enlarged scrotum.

The Western Way continues across Mayo for another 130 km, up past Croagh Patrick and Westport, northwards up Clew Bay, across the wilds of the Nephin Begs and the wilderness of Bellacorick bog and Sheskin forest to Ballycastle. But for us it was time to turn around and return to the Falls. We were going to Rosmuc, in South Connemara and another fishing lodge.

Screeb House on the shores of Camus bay is a vast fishing and hunting lodge. At 45,000 acres it is one of the largest hunting estates in the country and 16 red deer were introduced in 1996 after an absence of 150 years. They grew into a herd of about 150, managed skilfully by Paul Wood whose methods produced the largest stags in Britain and Ireland. Never confined and free to roam the mountains, bog, moor and forests browsing on bramble and ling heather they were selectively culled when old or frail. One stag known as The Sailor was so massive a team of 7 men with a quad bike couldn’t shift his carcass. They had to quarter him where he fell and weighed in at 50 stone, whereas the heaviest Highland beasts seldom exceed 20 stone.

The fishery includes 16 interconnected loughs and the number of rods allowed on the river beats and lakes is strictly controlled for conservation of stocks. The hatchery produces 50,000 smolts a year, like Delphi, released into the pristine waters over the estate.

The house was built in 1860 for Thomas Fuge and was bought by the Berridge family, owners of Ballynahinch Castle, brewers from London who managed to accrue 160,000 acres of co Galway. Lord and Lady Dudley also spent a lot of time there when he was the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Lady Dudley, shocked by the poverty of the locals and lack of healthcare set up the Dudley Nurses.

Although not medically qualified she went on to do the same in Australia,and start a flying doctor service when her husband was appointed Governor General there in 1908, and later setup field hospitals on the 1st WW battlegrounds of northern France. Tragically while back at Screeb in 1920 she went for a swim from the harbour there and was found drowned later.

I’d spotted a dotted line on the Ordnance survey map of the area, a track, that crossed the lake studded empty wastes of the bog from Rosmuc to Maam Cross, a distance of more than 10km. Before the coast road was built in the 1850’s this was the only route there was and we followed it into the past.

The big sky and wide horizon opened up, with long sighted views across the vastness to the Bens and Maumturks beyond. The rough and rocky path took us down to the shores of Lough an Oileain, where in Penal days the mass would be celebrated secretly.

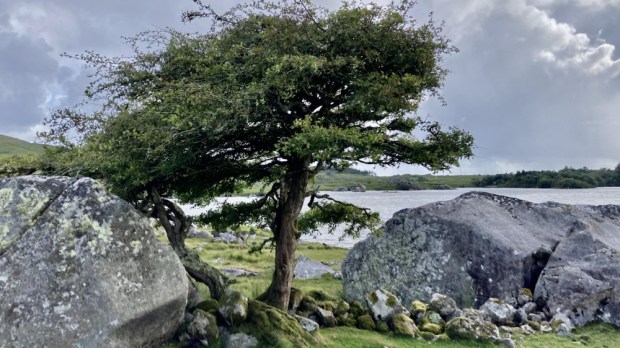

We followed the traces of the past, drawn towards a place that resonated with the ghosts of lives lived long ago. Tim Robinson, map maker and Connemara geographer, described it better than I could in his book A Little Gaelic Kingdom.

It was truly a place of melancholy spirit but with a strength and perseverance to survive in the hardest of times. The hawthorns were remarkable in their endurance but were at the end of their lives as witness to relentless hardship.

The wilderness here is to me an irresistible force and I like to think that I will be back to continue to follow the dotted line to Ma’am Cross but for now it was time for us to return to the pampered life of a house guest in a Connemara sporting lodge.

Fair play to Nano Nagle- May her good work continue. We moved off to the neighbouring village of Killavullen for the night and more riverside rambles before heading northwest, back to the Awbeg at Doneraile. The richness of the land was such a contrast to our surroundings in the Wild West with vast fields of ripening cereal and huge farm sheds for all the straw and grain.

Fair play to Nano Nagle- May her good work continue. We moved off to the neighbouring village of Killavullen for the night and more riverside rambles before heading northwest, back to the Awbeg at Doneraile. The richness of the land was such a contrast to our surroundings in the Wild West with vast fields of ripening cereal and huge farm sheds for all the straw and grain.

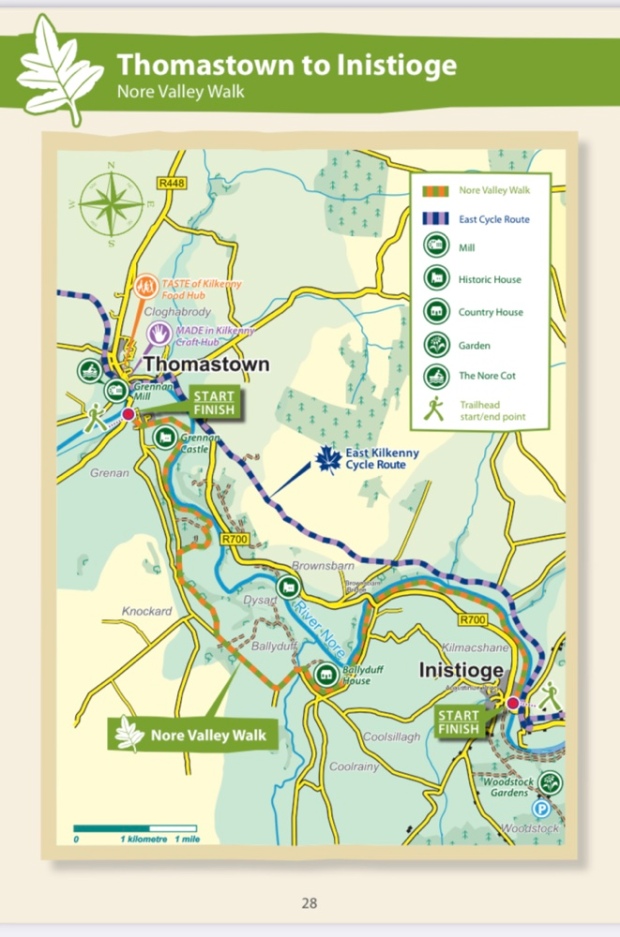

A heatwave upon us we decided on a watery walk shaded by mature hardwoods growing from the fertile soils of the south east. Having boated and hiked both the Barrow and the Suir it was to the last of the three sisters we headed – the Nore.

A heatwave upon us we decided on a watery walk shaded by mature hardwoods growing from the fertile soils of the south east. Having boated and hiked both the Barrow and the Suir it was to the last of the three sisters we headed – the Nore.

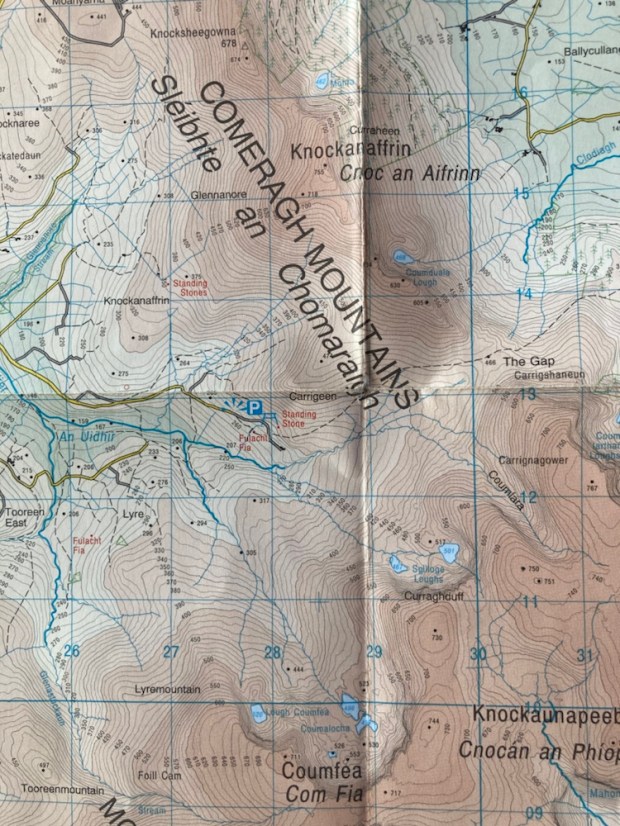

Just south of Clonmel you leave Tipperary and enter Waterford and the ground before you rises up into one of the most beguiling mountain ranges in Ireland, the Comeraghs ( from Cumarach- full of hollows). Named after the glacial coums or corries nestled into the sheltering arcs of towering cliffs of old red sandstone, their drama has drawn walkers for a long time and I’d been trying to get into them for years. With the dry and sunny weather due to end soon I took off for a couple of days exploration.

Just south of Clonmel you leave Tipperary and enter Waterford and the ground before you rises up into one of the most beguiling mountain ranges in Ireland, the Comeraghs ( from Cumarach- full of hollows). Named after the glacial coums or corries nestled into the sheltering arcs of towering cliffs of old red sandstone, their drama has drawn walkers for a long time and I’d been trying to get into them for years. With the dry and sunny weather due to end soon I took off for a couple of days exploration.

Cows and sheep grazing, insects and birds on the ponds and wild growth of heathers, grasses, lichens and mosses all testified to recovery. The paths followed the miles of old railway track, laid down to facilitate the removal of 1000 tonnes of ground a day. 10km of new roads have now been made for phase 2, complete next year and doubling the number of turbines and producing an additional 83MW of clean energy.

Cows and sheep grazing, insects and birds on the ponds and wild growth of heathers, grasses, lichens and mosses all testified to recovery. The paths followed the miles of old railway track, laid down to facilitate the removal of 1000 tonnes of ground a day. 10km of new roads have now been made for phase 2, complete next year and doubling the number of turbines and producing an additional 83MW of clean energy.