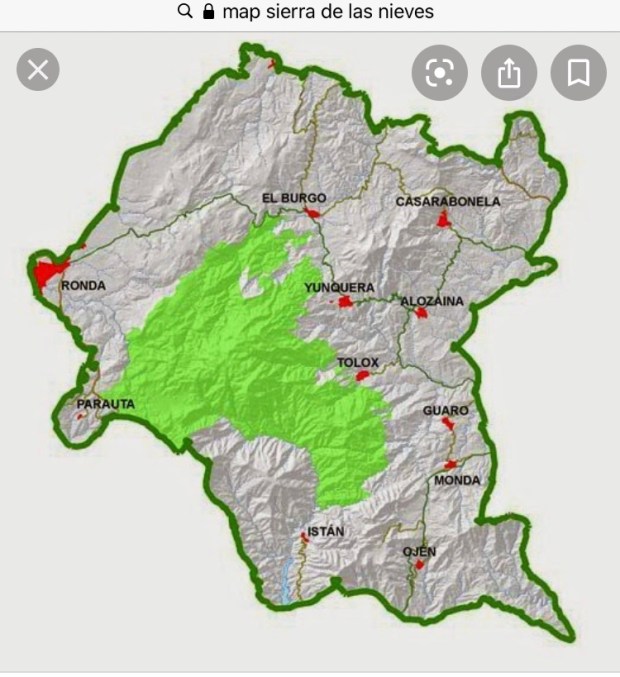

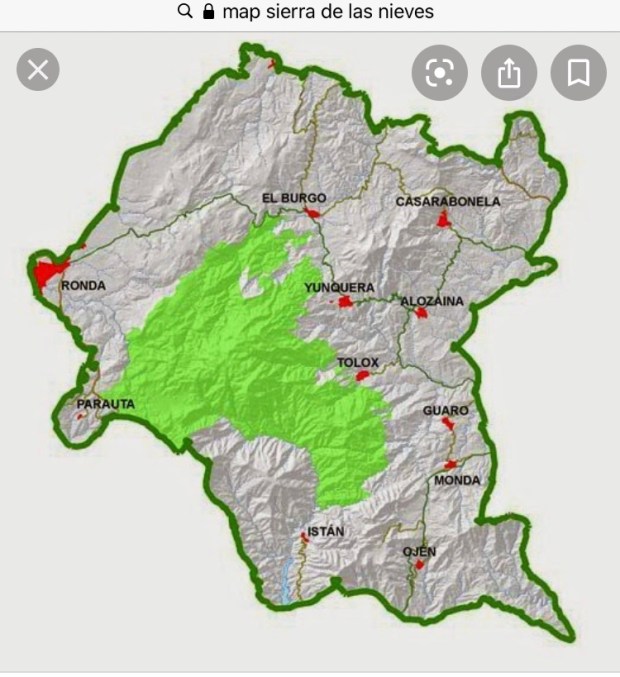

A short journey of 15 km inland from the busy beaches and constant consumerism of Marbella on the Costa del Sol takes you to another world and the southern edges of the Parque Natural Sierra de las Nieves, a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve of nearly 100,000 hectares.

We made 2 hiking trips to explore the park between lockdowns after finding a long distance route, the GR 243, traverses the area from Istan in the south to Ronda in the north, over 6 sections and 122 km with a couple of variants.

We discovered we could do a 3 day triangle at the southern end and avoid transport complications.

Leaving our car near the Cerezal recreation area outside of Ojen we headed off on the GR variant and PR-A 167 route to Istan.

Ojen is one of the half dozen or so tranquil whitewashed villages and towns surrounding the park that were Moorish strongholds and still retain the crumbling fortresses of the reconquest era. With a wealth of minerals to exploit in the Sierra’s rocky interior the area was at the forefront of the industrial revolution in the 19th century. Hard to imagine nowadays when the decreasing population is drawn to employment down on the coast. Ojen’s main export now is a anise like spirit that bizarrely is particularly popular in New Orleans during Mardi Gras.

First few Kms were a rocky scramble up a dry stream bed and on a lovely path through a forest of pine with distinctive peaks rising above us. As the sun climbed and the heat rose so did the strong scents of pine needles and oil and I recalled the studies of the positive effects on the mental and physical health of “forest bathing” and the phytoncides, the chemicals emitted by the trees.

Emerging onto a forestry track on a high level plain planted with a variety of conifers and eucalyptus we passed a number of weekend walkers and a few parties of mushroom gatherers- all of whom had dogs that made us wonder if they used them to sniff out the fungi. They seemed to have been successful anyway and had baskets brimming with a mushroom similar to chanterelles that we were told bled red juice when cut with a knife.

Climbing a narrow rocky path up and over the ridge we found ourselves in wild untamed country with a vista of peaks disappearing into the cloud. The extent of the park became apparent. When originally designated in 1989 the Natural Park was 78sq miles and this was increased to cover 362 sq miles on achieving World Biosphere Reserve status in 1995.

We had passed signs warning us that our route demanded physical fitness, good mountain orienteering skills and experience and we began to see why when we started to clamber down the descent towards Istan on a, luckily dry, stream bed, the Canada de Juan Ingles gorge. Tricky going but rewarded by the magnificent views and flora, particularly the dwarf or fan palms and the masses of aromatic rosemary, thyme and lavender.

Istan is a place of water boasting numerous springs, fountains, pools, the rivers Verde and Molinos and a network of ancient irrigation channels built by the Moors. Once a place of great wealth with a thriving silk industry and forests of white mulberry, walnuts and oak, hillsides of vineyards producing wine and raisins that bought ships from France and England, all changed when after the rebellion and defeat of the Moricos ( Muslim converts to Christianity) in the mid 16th century the area was practically uninhabited until Christian settlers from other areas in Spain took over the old Moorish properties.

The next leg was a longer but easier 20km trek on mostly good tracks to Monda, over the Canada del Infierno and the high point of Puerto de Moratan at 600m.

Leaving town on a road passed the Nacimiento ( the birth or spring) of the Rio Molinos we headed into the wild hinterland with remote houses dotted here and there in the folds of the hills.

A tiny tree had been dressed for Christmas on the track that took us eventually up to the pass and a helipad- maybe for forest fires or mountain rescue. The landscape seemed to hold more moisture with lush grasses accompanying the palms.

From the Puerto it was a long descent alongside a massive fenced and gated estate of forest, orchard and arable strips between rosemary covered scrubland.

Crossing a river bed on the outskirts of Monda we climbed an ancient cobbled track before arriving into town to find our bed by the loofah plants.

The final leg of the triangle back to Ojen was a 16 km combination of GR243 and GR249, my old trekking companion the Gran Senda de Malaga. Starting off on the trail we had arrived into town on, we soon diverted under the road and into a forested area, eventually turning off onto a steep overgrown track that climbed up and over the mountains separating the two towns.

The views all the way down to the coast awaiting at the top made up for the scratching and effort involved in getting there and the difficulty in scrambling down the steep path back down to the Cerezal recreation area and eventually , with relief, the hire car, still safely where we left it.

The Sierra is very shortly to become designated a National Park, the 1st in Malaga province- 3rd in Andalucia and 16th in Spain, an upgrading to the premier league of protected environments that will mean an increase in investment in infrastructure to develop responsible tourism such as visitor and nature education centres, lookout points and outdoor leisure facilities. The dozen or so towns in the area are hoping this will help stem the flow of outward emigration and bring increased employment possibilities.

The logistics of returning from a multi day linear walk put us off returning to the GR 243 so our next trip to the area was centered in a couple of spots from which we rambled on a number of routes deep into the Parks interior.

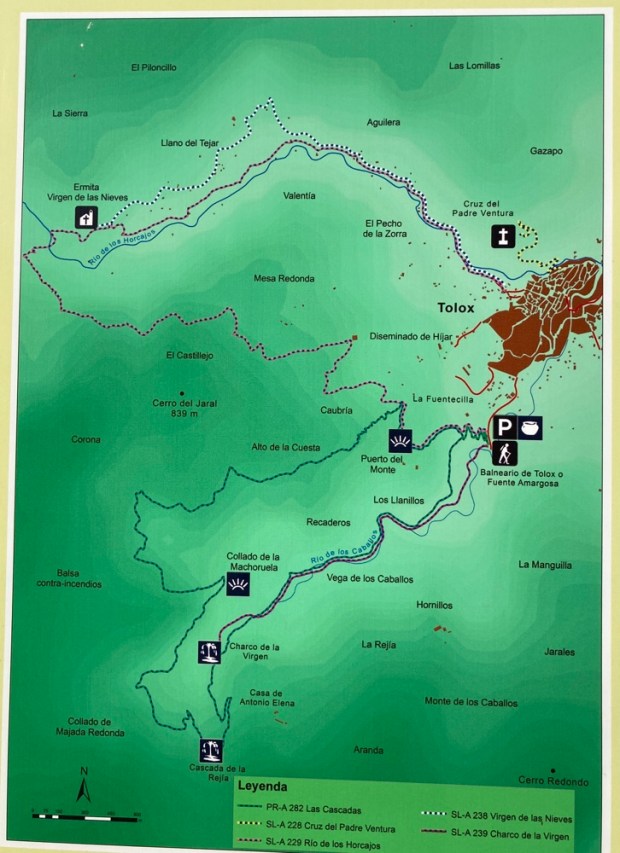

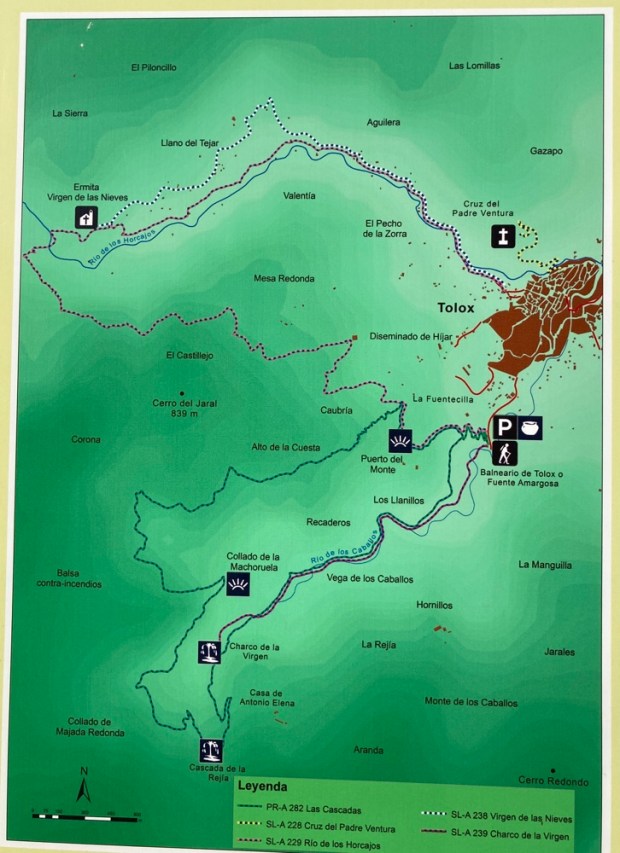

Staying at a mountain hotel high above the town of Tolox for a night enabled us to tackle a couple of great trails, the first of which, the PR-A 282 route to Las Cascades, took us in a 11km loop around the steep slopes, deep valleys, gullies, ravines and precipices typical of the landscape with the added attraction of some mighty waterfalls in full flow after some days of rain and snow.

Starting off from the Puerto del Monte we climbed a zig zag track way marked with yellow and white dashes up through the red peridotite rocks this area is renown for. The lower altitudes of the Sierra are made up of the worlds largest massif of this rare rockform. The impervious nature of the rock holds the water that nurtures the lush vegetation and creates the dramatic cascades.

Somewhat alarmed at the signs warning of “fording rivers, landslides and falling into voids” we carried on around the deep creases and folds to a series of cascades where the more adventurous enjoy canyoning and we were satisfied with sitting and picnicking.

Beautiful, and if it had been a bit hotter I might have managed a cold power shower. Instead we descended to the valley floor and tried to stay dry footed while crossing backward and forward over the river before climbing again to our starting point.

In the morning, stepping out of the Hotel Cerro de Hijar, we were off on the SL-A 229 Rio de los Horcajos, supposedly only 9 or 10 km but , as usual, working out a fair bit more. Another loop, this one took us up and over a pass to a steep sided valley that we descended into to follow the river down into Tolox and up again to the hotel.

Climbing over the pass we could see the snowy peaks of some of the parks higher mountains including La Torrecilla at 1920 m ( 6300ft) Malaga’s highest. On its limestone slope, at 1670m, is the entrance to the 3rd deepest cave shaft in the world, dropping vertically over 1000m. Known as GESM it is one of a great many caves and shafts in the limestone mountains and a great draw for potholers and cavers.

The steep valley slopes were covered with ancient, much pollarded chestnuts which along with holm, cork, gall and Portuguese oaks and pine carpeted the Sierra up to the snow line.

We followed a beautiful old stone track down through the shrub to the Rio Horcajos. The whole area is covered with a network of trails, as is much of rural Spain. These paths between villages have been used for hundreds of years by shepherds, goatherds, muleteers, charcoal makers, herders and travellers of all kinds forming a web of communication and information.

It wasn’t long before we came to a recreation area at the hermitage of the Virgin of the Snows where natural springs emerged from the ground to join the river that we followed into Tolox on a verdant path between rampant crops.

The river had once supplied the power for many mills in Tolox , for grain and olive oil, but nowadays the local sulfur rich waters of the Balneario o Fuente Amargosa emerge at a constant 21* and supply Spain’s only medicinal spa. Famous for the treatment of kidney and urinary problems by drinking and respiratory disease by inhaling the mildly radioactive vapours you need a doctors prescription for a 2 week treatment. The building was our last stop before a final leg aching climb back up to the hotel and car. Time to move on.

We were moving on to Finca las Morenas, an off grid farmhouse with accommodation run by a couple of Mediterranean garden designers who moved here after decades of working in London. In an isolated setting adjoining the Natural Park outside of Yunquera the converted sheds next to the 300 yr old farmhouse had been tastefully and thoughtfully renovated and featured many environmentally friendly features designed to save water and power. Situated at above 700 m it was a perfect spot from which to explore the upper reaches of the Sierra.

Our first trek from the finca took us into the pines on a foresters track that took us slowly up another 500 m to the Cueva del Aqua, the cave of water, and into the snow. Obviously the Sierra de las Nieves, the “Mountains of the Snows” have a reputation for getting a fair bit of the white stuff and there had been some heavy falls before we came.

This walk would also bring us for the first time into stands of the tree the park is famous for, the Abies Pinsapo, the Spanish Fir endemic to this region. “Discovered “in 1837 it is a botanical relic of the pre glacial period that by the 60’s was in danger of extinction due to felling but under protection they now cover an area of 5000 hectares. Some are National Monuments and hundreds of years old and are the emblem or symbol of the Natural Park but unfortunately a more subtle and pernicious effect of mankind’s damage to the environment could still be their downfall. An invisible fungus has been attacking and killing the trees whose natural resistance is thought to have been weakened by climate change and ecologists are calling for a seed bank to be created to ensure survival of the species.

We reached the cave after about 6 km and carried on up to a picnic spot with a view before returning to explore it on our way back down to the finca. Deep enough to provide plenty of shelter for goatherds and their flocks the walls bore the smoke stains of countless fires.

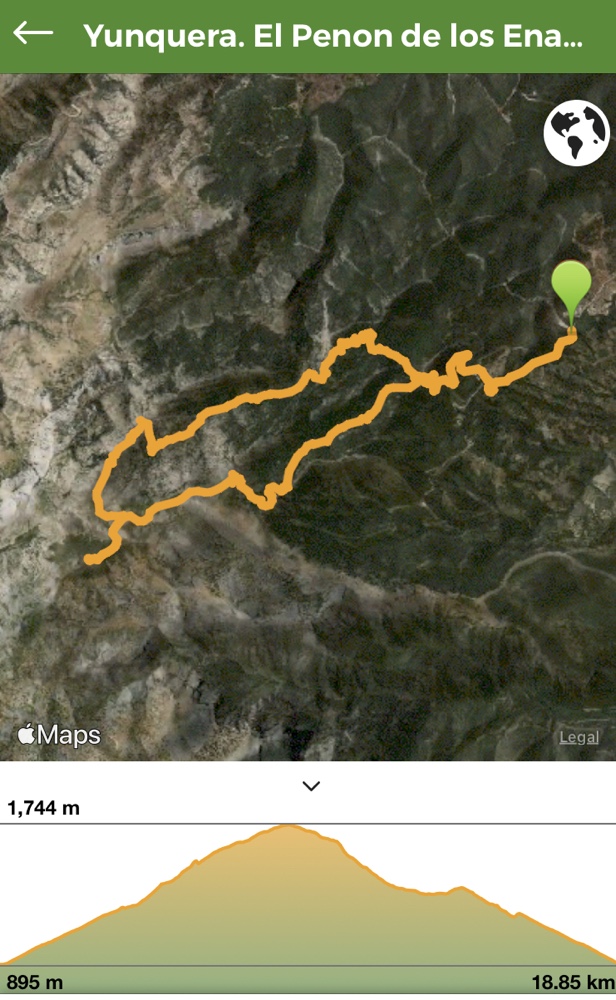

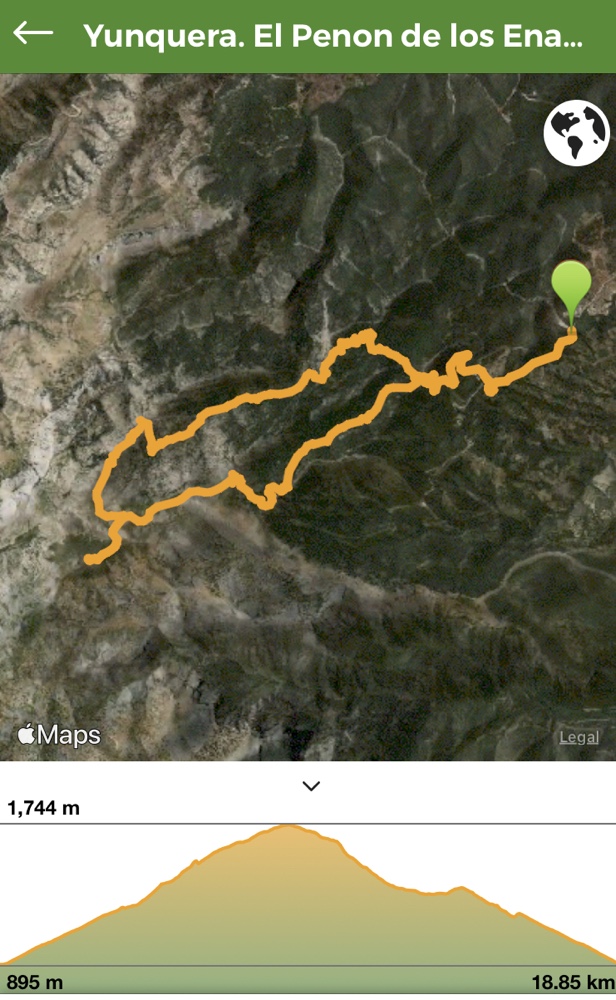

Next day we set off to drive up to the Mirador Puerto Saucillo above Yunquera to do a hike up to Penon Enamorados ( Lovers Crag/Rock) the second highest peak in the Sierra at 1760m. Unfortunately the road up had been blocked half way up by local police adding another 6 km and 300 m ascent to our days walk.

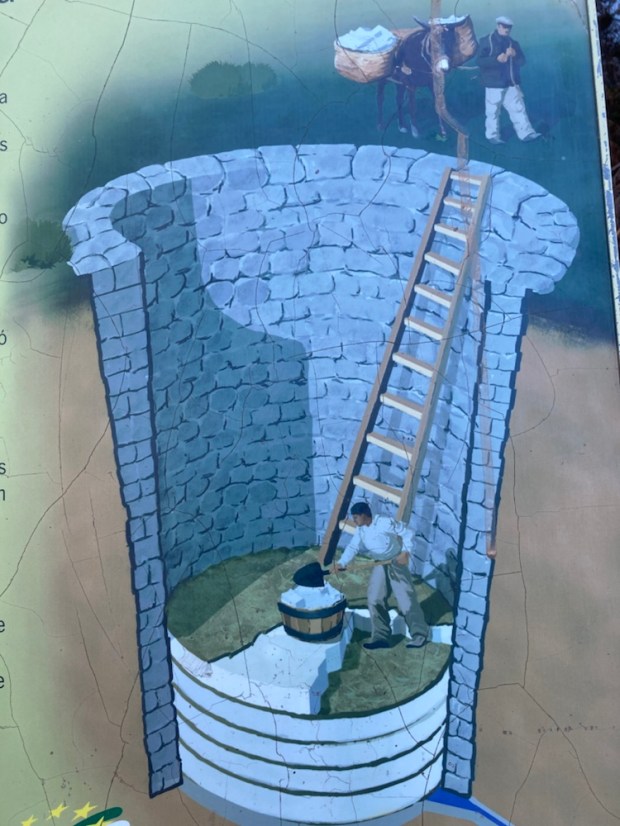

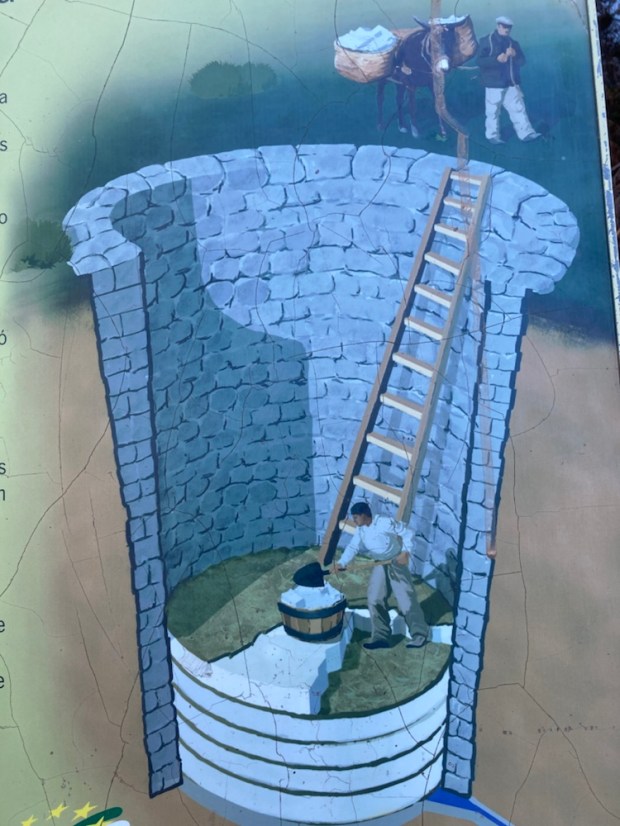

After a chocolate break on reaching the mirador at 1240m we set off on a yellow and white marked route the PR-A 351 and were immediately immersed into the snowy landscape that had long been a source of industry with the building of snow pits and the subsequent transportation ,by mule ,of snow and ice all over the province.

After a chocolate break on reaching the mirador at 1240m we set off on a yellow and white marked route the PR-A 351 and were immediately immersed into the snowy landscape that had long been a source of industry with the building of snow pits and the subsequent transportation ,by mule ,of snow and ice all over the province.

Chilly enough in the shade but climbing up out of the forest and onto more open rocky ground we were able to bask in the sun and take in the far ranging vistas.

The crisp clear air, bright sun and dazzling white snow made the views over the surrounding Sierras to the distant coast even more dramatic and awe inspiring as we climbed across an icy slope studded with occasional lonely Pinsapos and recently planted galloaks towards the “wedding cake” pile of Enamorados.

We were truly blessed with the conditions as we reached our goal at 1745m, happy to picnic at the bottom of the pile of rocks below the summit and take in the view of Torrecilla, another 200 m higher. Another time.

Our return leg to the mirador was on a smaller track across a coll, and along a ridge and then down to the bottom of the valley, at times a slippery slide down snowy slopes. The trail, invisible beneath its white blanket was thankfully marked by many stone cairns, leading us back into the Pinsapo forest past tracks in the snow, the nearest we got to seeing any of the deer, boar, goat or muflon that are among the rich variety of fauna living in this wilderness.

We had discovered yet another area of Spain worthy of more exploration and will have to return. So many wonders. So little time.

A dramatic walking route opened in the Parque Natural de Tejeda, Almijara y Alhama in October 2020 after many months construction. An old path following irrigation canals and pipes into the mountains above Canillas de Aceituno was transformed with a steel and timber suspension footbridge and other hanging walkways fixed to sheer cliff faces.

A dramatic walking route opened in the Parque Natural de Tejeda, Almijara y Alhama in October 2020 after many months construction. An old path following irrigation canals and pipes into the mountains above Canillas de Aceituno was transformed with a steel and timber suspension footbridge and other hanging walkways fixed to sheer cliff faces. The €600,000 investment is hoped to bring in much needed tourist revenue to the area and it seems to be paying off. The day we tackled it the town at the start was busy with people with poles, and the pandemic has led to many more people exploring the vast natural areas away from the more crowded costa. In fact some places such as the Caminito del Rey and El Torcal have become a victim of their own success with long queues, traffic jams and overcrowding but we’ve always found that away from the honey pots Andalucia has space aplenty.

The €600,000 investment is hoped to bring in much needed tourist revenue to the area and it seems to be paying off. The day we tackled it the town at the start was busy with people with poles, and the pandemic has led to many more people exploring the vast natural areas away from the more crowded costa. In fact some places such as the Caminito del Rey and El Torcal have become a victim of their own success with long queues, traffic jams and overcrowding but we’ve always found that away from the honey pots Andalucia has space aplenty.

We’d been meaning to come here for a long time and the Parque had been generous in showing us its splendours. Perhaps we’d been lucky with the weather or perhaps, as the emptying reservoirs and dieing Pinsapo indicated, things were changing. But as the weather worn limestone, Neolithic cave paintings, Roman roads, Moorish castles and abandoned cortijos show,change is a constant, and hopefully the beauty will survive.

We’d been meaning to come here for a long time and the Parque had been generous in showing us its splendours. Perhaps we’d been lucky with the weather or perhaps, as the emptying reservoirs and dieing Pinsapo indicated, things were changing. But as the weather worn limestone, Neolithic cave paintings, Roman roads, Moorish castles and abandoned cortijos show,change is a constant, and hopefully the beauty will survive.

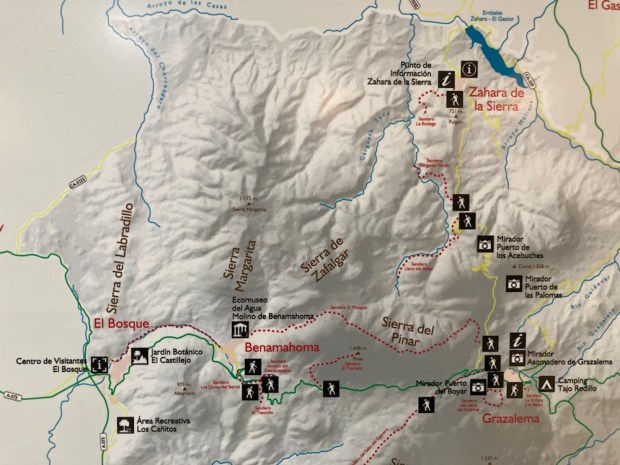

Moving on into the park in the morning we drove up to the Area Recreativa Cuadros and walked through the river side oleander forest that housed many shady picnic tables and benches and up on paths of needles and stone into the pines.

Moving on into the park in the morning we drove up to the Area Recreativa Cuadros and walked through the river side oleander forest that housed many shady picnic tables and benches and up on paths of needles and stone into the pines.

As the winter storm clouds gather over Ireland and the temperature and raindrops fall the call to Spanish adventures cannot be ignored. A 30 hour intermission in a cramped cabin surrounded by a swelling mass of moving ocean and we were once again driving into the mountains heading south.

As the winter storm clouds gather over Ireland and the temperature and raindrops fall the call to Spanish adventures cannot be ignored. A 30 hour intermission in a cramped cabin surrounded by a swelling mass of moving ocean and we were once again driving into the mountains heading south.

After a chocolate break on reaching the mirador at 1240m we set off on a yellow and white marked route the PR-A 351 and were immediately immersed into the snowy landscape that had long been a source of industry with the building of snow pits and the subsequent transportation ,by mule ,of snow and ice all over the province.

After a chocolate break on reaching the mirador at 1240m we set off on a yellow and white marked route the PR-A 351 and were immediately immersed into the snowy landscape that had long been a source of industry with the building of snow pits and the subsequent transportation ,by mule ,of snow and ice all over the province.

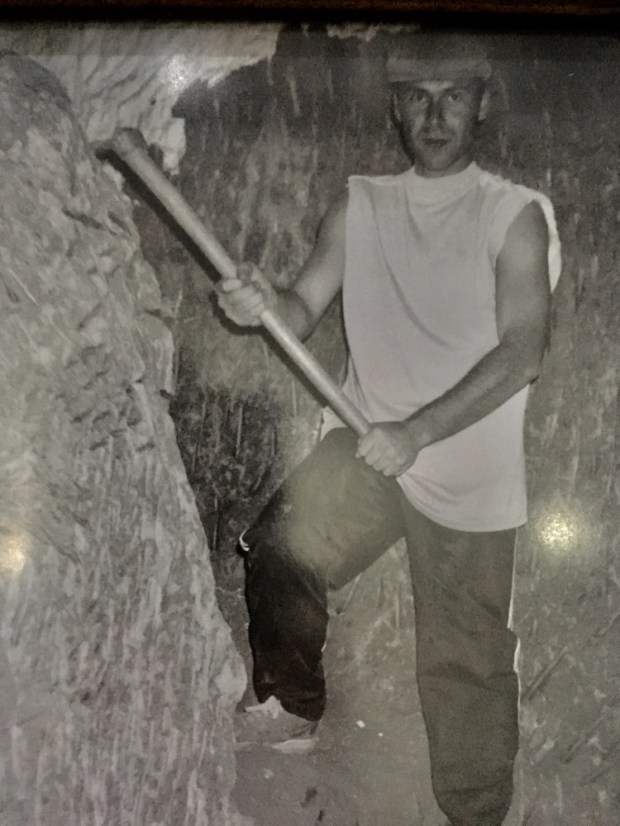

The middle floor was laid out as a home of maybe 50 years ago and the final, upper floor was stuffed full of ethnological artifacts.

The middle floor was laid out as a home of maybe 50 years ago and the final, upper floor was stuffed full of ethnological artifacts.