About an hour drive or 100 km north west of Tabernas in southern Spain, the last Badlands we explored, lies another extraordinary landscape.

Designated an UNESCO Global Geopark in 2020 the 4,722 sq km park is a harsh semi desert of deep broad depressions, gorges, canyons, gullies and ridges with rocky outcrops and cliffs. For millions of years a vast inland lake was formed by rivers with no exit to the sea, hemmed in by a ring of mountains. Layers of sediment built up which have been exposed over the last 500,000 years as the rivers forced a way to the sea and began the erosion process that has created this surreal environment.

We had heard from friends that the area was rich in hot springs and that there was a mass of Neolithic dolmans left by the first hominids to reach Europe and had wanted to visit this relatively unvisited and unpopulated place for awhile, and Sally’s birthday was a good excuse to plan a trip.

On the Camino Mozarabe from Almeria to Granada a few years ago we had walked through the southern edge of the park and had loved the area around Guadix and Purullena with all the cave houses and weirdly eroded hills. I remembered we passed a hotel that boasted a hot spring medicinal spa and were very envious of its clientele. I found it online, and booked a room for the birthday. Memories of our hike there seeped into our consciousness as we drove through a sandy wooded area on a track marked with the yellow arrows of the Camino and up to the Carcavas de Marchal, a viewpoint looking out over the Purullena badlands.

After a deep cleansing and healing in the hot mineral waters of the spa and a restful night we headed north to explore the phenomenon of the Travertinos de Los Banos de Alicun, another thermal spring.

The thermal spring here, rich in calcium carbonate, emerges from deep underground, travelling up through a fault line to reach the surface at 35*C. For the last 200,000 years the strongly mineralised waters have been flowing downhill, creating a channel of travertine as they go.

The channel of calcium carbonate rich waters precipitate, slowly building up and covering the plants and grasses that thrive there, fossilising them.

The waters were useful to Neolithic people living there who encouraged the flow towards their camping places and when the channel got too shallow it was dug out to deepen it.

Over the millennia the walls of the acequia have grown into a towering bank 15m high and 4m wide at the base. It snakes through a fascinating area of rich vegetation and dripping water next to parched eroded desert.

We followed the channel for over a km before arriving at a spot where the walls had been breached, the water running out to form a warm waterfall.

Returning to the source of the stream at the spa hotel closed for the winter we picnicked before driving on to Gorafe and up to the high plateau above the Gor river valley. This was one of the areas with the heaviest concentration of dolmens in Europe.

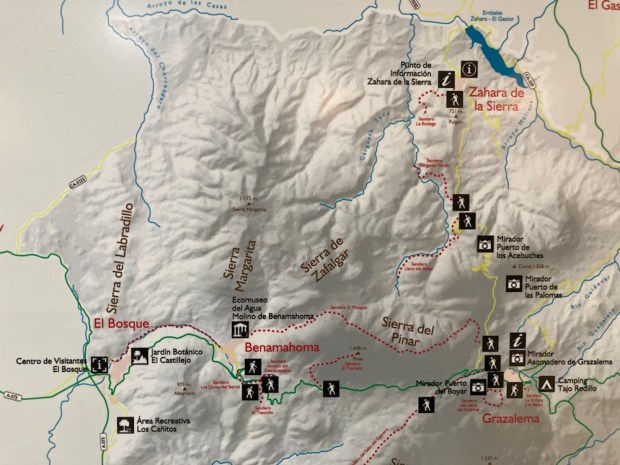

At a height of 900m above sea level, overlooking the arid Badlands, it is hard to know why the early settlers chose this place to build over 240 megalithic burial chambers, passage graves and corridor tombs. The dolmens were built over a period of about 1500yrs from 3000 BC when the conditions were good for the Neolithic families to establish the many settlements in the Gor river valley. The climate was wetter and cooler than today and the valley soils were fertile.

We drove on along the plateaux on a rough track admiring the deep gullies with arid sandstone buttes between us and the high plateaux on the other side of the valley. The rock is horizontally banded with red, yellow , grey and white strata. A stunning, beautiful and cruel landscape.

Our accommodation for the night was perched at the edge of the plateaux at the end of the track. Remote in the extreme, a self contained, off grid, designer converted shipping container, run on solar panels with all its functions controlled by an app on my smartphone.

With an electric toilet that incinerated the waste, a water recovery system that could extract 250l of water a day from the air and a bank of lithium batteries for storing the power from the solar panels this was the first of what they hope will be a collection of pods dropped into stunning locations. Fully autonomous and transportable the eco- hotel has no foundation, uses no local resources and aims to have no environmental impact.

It was a spectacular place to stay, very cleverly designed to use all of its 35sq m space well. The glass wall of the bedroom afforded a stunning view of the star studded night sky and in the morning the valley below was shrouded in low cloud.

It was hard to leave but we had more to look forward to on the top of the plateau opposite and after check out we explored some of the area, crossing the stony almond fields and discovering some old shepherds cave houses and animal pens dug out of the sandstone butte.

They were a little rougher than the caves developed for tourist accommodation we came across further on , situated high above Gorafe town.

The next development we discovered way out in the middle of nowhere was an observatory. A new educational and Astro tourism centre taking advantage of the near zero light pollution. This has been designated a ” dark sky zone” and is the perfect spot for star gazing as we had discovered in the podtel. As it happened there was an all night programme of events to be held there that night but as you had to book in advance, pay €30 each, and stay up all night to listen to Spanish we didn’t understand we decided- not for us.

( Not my photo)

( Not my photo)

Besides we didn’t want to abandon our futuristic home for the night, which we had spotted on the horizon. La Casa Del Desierto.

Another off grid, autonomous space raised up on a mound containing services, this one also afforded awesome views out over the corrugated hills and folded landscape below the plateau’s rim. The three sided totally glass clad structure gave no privacy and had been fenced off from the curious eyes that had bothered some of the earlier guests.

An extraordinary space in an extraordinary place- the three small interior spaces of bedroom, bathroom and kitchenette were surrounded by a verandah under an overhanging roof, giving all day shade. But with no cooking facilities it was not a place to stay for long and so our one night was enough.

Before dark we hiked over to another look out spot at the end of a narrow path to the point of the bluff, passing some serious campers ready for this environment.

We made it back before the sun disappeared in a glorious palette of colour and the stars came out.

In the (25*c mid December) morning we sat at the table but not on the one legged high chair gazing out at the bizarre surroundings- soaking in the dry, the heat, the emptiness and the silence- before reluctantly getting into the car and turning for the west. Towards Ireland and home.

Crossing the broad flattish area of Los Barrerones we started to descend and the awesome views of the Circo de Gredos made the effort of the climb a very reasonable price to pay.

Crossing the broad flattish area of Los Barrerones we started to descend and the awesome views of the Circo de Gredos made the effort of the climb a very reasonable price to pay.

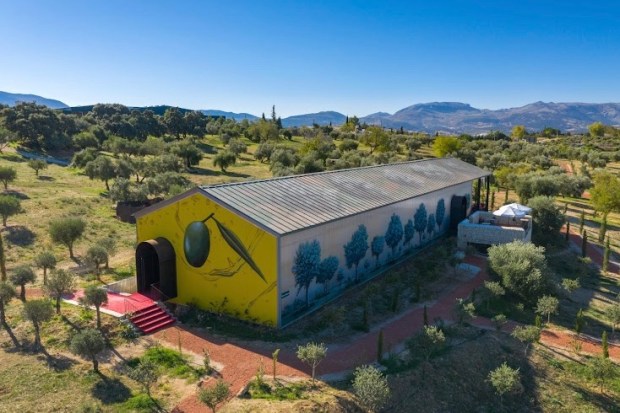

For days we had been walking through a very dry Andalucia and yet the growth of new irrigated plantations continues. The region produces 80% of Spain’s and 30% of global olive oil. 900,000 tonnes a year. Plus 380,000 tonnes of table olives. They take up 85% of the land. 70 million trees- 1.5 million ha- the biggest tree plantation in Europe. The defining historical, cultural, agricultural and economic feature of this huge area of Spain. But there are many danger signs.

For days we had been walking through a very dry Andalucia and yet the growth of new irrigated plantations continues. The region produces 80% of Spain’s and 30% of global olive oil. 900,000 tonnes a year. Plus 380,000 tonnes of table olives. They take up 85% of the land. 70 million trees- 1.5 million ha- the biggest tree plantation in Europe. The defining historical, cultural, agricultural and economic feature of this huge area of Spain. But there are many danger signs.

A dramatic walking route opened in the Parque Natural de Tejeda, Almijara y Alhama in October 2020 after many months construction. An old path following irrigation canals and pipes into the mountains above Canillas de Aceituno was transformed with a steel and timber suspension footbridge and other hanging walkways fixed to sheer cliff faces.

A dramatic walking route opened in the Parque Natural de Tejeda, Almijara y Alhama in October 2020 after many months construction. An old path following irrigation canals and pipes into the mountains above Canillas de Aceituno was transformed with a steel and timber suspension footbridge and other hanging walkways fixed to sheer cliff faces. The €600,000 investment is hoped to bring in much needed tourist revenue to the area and it seems to be paying off. The day we tackled it the town at the start was busy with people with poles, and the pandemic has led to many more people exploring the vast natural areas away from the more crowded costa. In fact some places such as the Caminito del Rey and El Torcal have become a victim of their own success with long queues, traffic jams and overcrowding but we’ve always found that away from the honey pots Andalucia has space aplenty.

The €600,000 investment is hoped to bring in much needed tourist revenue to the area and it seems to be paying off. The day we tackled it the town at the start was busy with people with poles, and the pandemic has led to many more people exploring the vast natural areas away from the more crowded costa. In fact some places such as the Caminito del Rey and El Torcal have become a victim of their own success with long queues, traffic jams and overcrowding but we’ve always found that away from the honey pots Andalucia has space aplenty.

We’d been meaning to come here for a long time and the Parque had been generous in showing us its splendours. Perhaps we’d been lucky with the weather or perhaps, as the emptying reservoirs and dieing Pinsapo indicated, things were changing. But as the weather worn limestone, Neolithic cave paintings, Roman roads, Moorish castles and abandoned cortijos show,change is a constant, and hopefully the beauty will survive.

We’d been meaning to come here for a long time and the Parque had been generous in showing us its splendours. Perhaps we’d been lucky with the weather or perhaps, as the emptying reservoirs and dieing Pinsapo indicated, things were changing. But as the weather worn limestone, Neolithic cave paintings, Roman roads, Moorish castles and abandoned cortijos show,change is a constant, and hopefully the beauty will survive.

As the winter storm clouds gather over Ireland and the temperature and raindrops fall the call to Spanish adventures cannot be ignored. A 30 hour intermission in a cramped cabin surrounded by a swelling mass of moving ocean and we were once again driving into the mountains heading south.

As the winter storm clouds gather over Ireland and the temperature and raindrops fall the call to Spanish adventures cannot be ignored. A 30 hour intermission in a cramped cabin surrounded by a swelling mass of moving ocean and we were once again driving into the mountains heading south.