Mougás to Pontevedra: 4 days : 87 km

A short 16 km day ahead planned luckily which will go easy on Sally’s feet and Emma’s first day, although we still started early enough, rising with the pilgrim tide from their beds at the albuergue. With no kitchen and milk that had turned to yoghurt our fresh supplies of Irish tea bags were of no use to us and without a bar or cafe for miles we walked off under the lightening sky to venture once again into Galician Connemara.

Again alternating yellow cycleway with sandy coast path for about 5 km we then turned up a forest track that became a wonderful and ancient stone paved track with the grooves of millennia of wheels carved into the granite. Stopping at the top after a short but sharp climb for restorative chocolate we admired the views over to the Cape Silleiro lighthouse.

Coming down towards the coast on the other side of the headland through the pine and eucalyptus I passed a farmer calmly leading some sheep to graze. The rugged mass of the Cíes islands came into view. Supposedly a fine example of eco tourism, the limited number of permit holding visitors can only stay at the one campsite although there are 3 restaurants and a well stocked shop to enjoy after exploring the sea and trails on this National Park.

Continuing on towards Baiona we passed a lovingly crafted 1940 faux castle tower with a fuente inside and in the plaza where we finally got a coffee, the Baroque Capela de Santa Liberata and the older 12 c church of Santa Maria.

Then through the historical quarter to the shore and ,following a cycle and walkway around it, soon reached the river Minor and crossed it on the beautiful Ponte da Ramallosa guarded by San Telmo, the patron saint of sailers.

A short climb past bars and restaurants to explore later lay our goal, the Hospederia Pazo Pias, where €15 secured a bed in a 17th century palace set in lovely grounds.

Gotta look after the pilgrims.

Pilgrims familiar from the night before joined us but we lost them again the next day when we decided to take another variant. This one avoided a lot of the suburban sprawl of Vigo, instead adding 2.5 km overall, but with an earlier finish for the day after 16 km or so. The start was a mix of urban and rural lanes and streets and woodland paths and tumbling streams.

There were lots of grand old houses indicating great wealth in the area and a fine selection of horreo, the traditional grain stores, wash houses and veg gardens.

A lovely stretch of stone paved woodland took us up to views over the Baiona and Vigo coast and the Cies islands. By coffee time we’d reached Priegue, stopping for refreshment before heading up into the forest again.

We had decided to stay at the Albergue O Freixo which meant leaving the main path and hiking another 5 km through the forest mostly on a trail that led past numerous old water mills and a couple of speeding bikers. Very beautiful and peaceful we stopped for a long rest amongst the towering eucalyptus.

Emerging from the greenery an open landscape of rocky ground and forest lay ahead. Hoping for the Albergue to come into view we were arrowed up and up and finally, gratefully, we arrived- at the same time as Angie, who, with the help of google translate, looked after us well.

The Albergue was also a thriving community centre with function room and fully equipped kitchen we could use to cook our dinner. There was also a community run bar which came in very handy and evening classes in Pilates and ,weirdly, bagpipe and drumming combo which didn’t come in quite so handy as the pipes and drums started just before bed time. They also prevented Austrian pilgrim Manfred from using a mattress in the classroom so as to spare us his monstrous snoring. So late that night the three of us in turn abandoned the dorm and transferred to the classroom- now only disturbed by the carousing of the community drinkers till the early hours.

With a biggish hike of 23/24km ahead in the morning we set off early and a bit bleary after a disturbed night. Down and down into the big city of Vigo as the lights went out and the sun came up.

The walk through the city was much more pleasant than we had feared, going through wooded parks and along riverside trails. Even close to the city centre there seemed room for gardens. And art.

On the north side we joined a route called the Senda da Auga that runs for 10 km beside a covered pipe taking water from the mountains to Vigo. Tarmac road to begin, with gorgeous views down the estuary to the sea, and then lovely shady woodland path with waterfalls and fountains. We passed and we’re passed by plenty peregrinos- so different to the empty Mozarabe route.

Emma listening for water, unsuccessfully.

At the end of the Senda it was a short 2.8 km to our bed in Redondela, housed in a beautiful old stone building nicely renovated into a municipal Albergue where the usual registration, shower, bed making, rest ritual was followed by the usual eating and drinking and more resting ritual.

A quieter night, an early rise, a chilly start- through the mix of old and new on the way out of town. Memorials, sculpture, gardeners, a stretch of busy main road, a climb through woods, and when needed, a funky cafe/ albergue for cafe and tostada.

From the cafe in Arcade we crossed the river Verdugo on the Ponte Sampaio and climbed again on ancient wheel rutted stone tracks through the forest and down through fields and vineyards, stopping for rest and chocolate by a feet soothing frog pool.

We were briefly diverted when crossing a new road construction, and then brought down through another section of towering eucalyptus forest to the Capela de Santa Marta where we gathered another stamp in our pilgrim passports.

A short distance further on was a split in the trail- the shorter by a km and with a cafe was beside a busy road, the longer was a peaceful 4 km stretch beside a tranquil stream. Although we had already decided on the river walk a postman stopped at the junction and proclaimed the virtues of the ” tranquilo” route to us. We had come together with the more popular Central route of the Portuguese Camino back in Rodondela and the Way was busy with peregrinos but many were chilling beside the shady stream.

Leaving the woods and water we went under the highway passing more graffiti and under the railway to arrive, after 19 km, at the Pontevedra albergue just as it opened, where a very stern and officious man had us all filling the dorm in order- top and bottom bunks- no anarchic freeform. Ah well, you’d put up with it for an €8 bed for the night.

And Emma’s won the prize bonds so big dinner tonight!

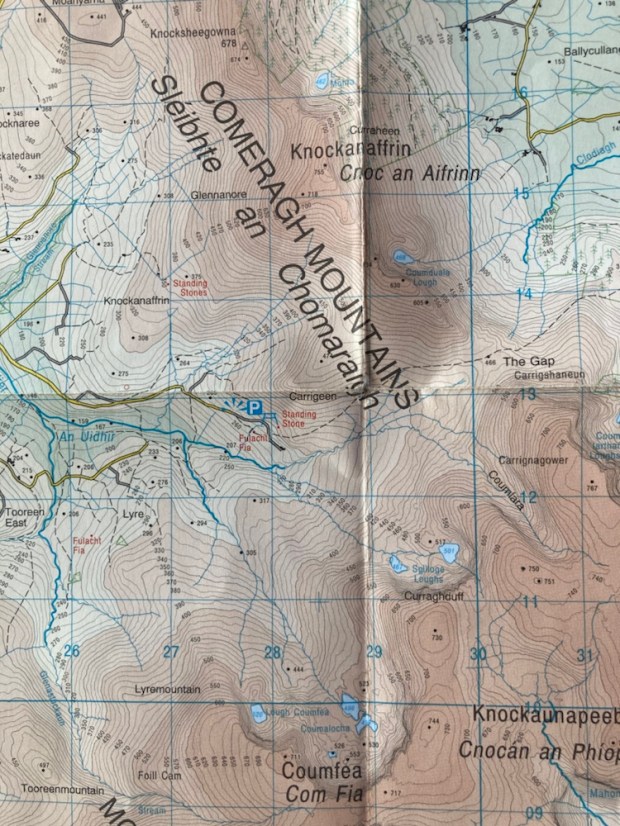

Just south of Clonmel you leave Tipperary and enter Waterford and the ground before you rises up into one of the most beguiling mountain ranges in Ireland, the Comeraghs ( from Cumarach- full of hollows). Named after the glacial coums or corries nestled into the sheltering arcs of towering cliffs of old red sandstone, their drama has drawn walkers for a long time and I’d been trying to get into them for years. With the dry and sunny weather due to end soon I took off for a couple of days exploration.

Just south of Clonmel you leave Tipperary and enter Waterford and the ground before you rises up into one of the most beguiling mountain ranges in Ireland, the Comeraghs ( from Cumarach- full of hollows). Named after the glacial coums or corries nestled into the sheltering arcs of towering cliffs of old red sandstone, their drama has drawn walkers for a long time and I’d been trying to get into them for years. With the dry and sunny weather due to end soon I took off for a couple of days exploration.

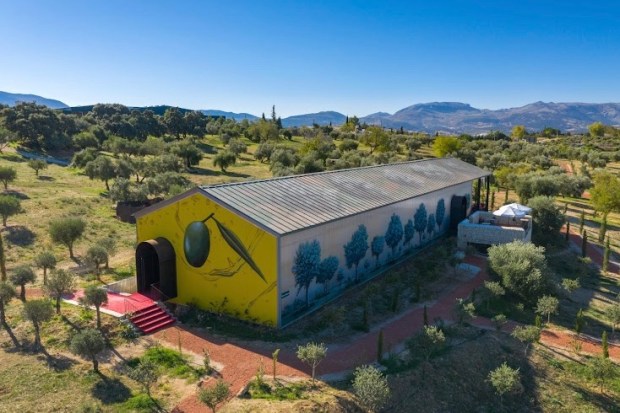

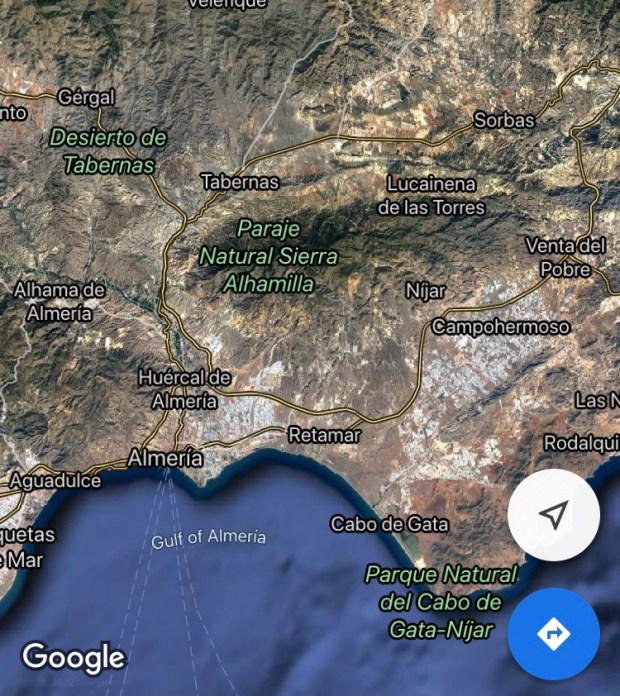

For days we had been walking through a very dry Andalucia and yet the growth of new irrigated plantations continues. The region produces 80% of Spain’s and 30% of global olive oil. 900,000 tonnes a year. Plus 380,000 tonnes of table olives. They take up 85% of the land. 70 million trees- 1.5 million ha- the biggest tree plantation in Europe. The defining historical, cultural, agricultural and economic feature of this huge area of Spain. But there are many danger signs.

For days we had been walking through a very dry Andalucia and yet the growth of new irrigated plantations continues. The region produces 80% of Spain’s and 30% of global olive oil. 900,000 tonnes a year. Plus 380,000 tonnes of table olives. They take up 85% of the land. 70 million trees- 1.5 million ha- the biggest tree plantation in Europe. The defining historical, cultural, agricultural and economic feature of this huge area of Spain. But there are many danger signs.