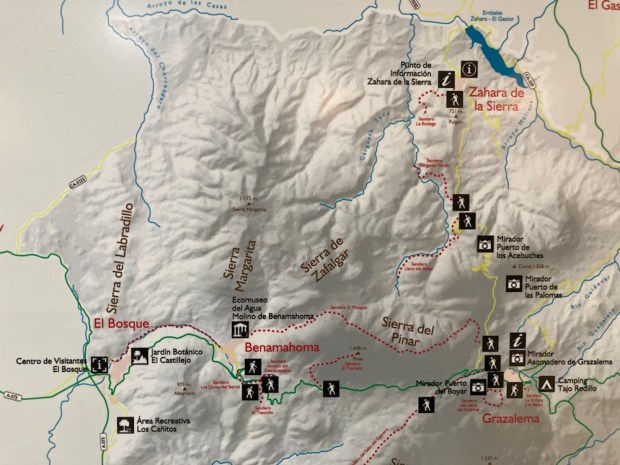

South of Seville, east of Cádiz lies the Parque Natural Sierra de Grazalema, a 500sq km UNESCO Biosphere. 10 ” white villages” of Moorish origin are tucked defensively into the rugged folds of the high limestone peaks, 20 of which surpass 1000 m. The Sierra is the western tail end of the Cordillera Betica, the range we were hiking in 300km further east in the Sierra Mágina. Like the Mágina region this was the frontier between Muslim and Christian territories in the 13th to 15th centuries which explains the formidable positioning and also the names of the many towns called ” ….de la Frontera”.

Although relatively small the park is immensely varied. Towering bald grey peaks and vertical cliffs lead down through deep clefts and gorges, through thick forests of holm, gall and cork oaks to grape and nut and olive plantations with lush grassy meadows and fields of grain.

The mountains are the first high ground encountered by the wet winds from the Atlantic and the rain that is dumped on them make this the wettest area in Spain and the greenest in Andalucia. The favourable micro climate enables 1/3 of all plant species in Spain to thrive here, many endemic, which in turn encourages a wealth of bird life. Referred to as an ornithological wonderland the sky is often full of wheeling raptors soaring on the updrafts above the cliffs.

Although the land is productive with cow and goat cheeses, honey, wine, oil, grain and regional crafts of wool, cork, leather and esparto grass are still strong the area has been through hard times. A testament to the rural exodus of the mid 20 th century are the forlorn and crumbling cortijos returning to the land from which they were built.

Tourism, particularly of the green variety, is helping to keep the region vibrant and droves descend on holidays and weekends from far and wide to explore and enjoy the natural beauty. So much so that permits are needed to hike 4 of the trails in the inner 30sq km “area de reserva”, the most spectacular and protected part of the park and even these are normally closed completely from July to October.

We managed to secure permits for 3 of the 4 walks at the Park info centre in El Bosque and with maps of other routes for later we set off on our first, the Sendero El Pinsapar.

From the parking and picnic area of Las Canteras high up on the road that twists and turns it’s way over the mountains from Grazalema to Zahara de la Sierra the 11km route climbs up through a pine forest planted to hold back the erosion the areas high rainfall can cause. The ground was coated thickly in the long needles cast off by the trees and we wondered if their acidifying effect on the limestone beneath would eventually create a neutral ph loam.

After a climb of around 300m we reached a pass at Puerto de las Cumbres, a natural gateway to the northern flank of the mountain where the route continued west on a much more level gradient half way between the valley floor below and the summits high above us. Pico San Cristobal stood out dramatically with fast moving cloud scudding across the blue around it and the mighty buttress of El Torreón, the highest peak of the Parque at 1654m loomed in the distance. A strong buffeting wind forced us on along a rocky path toward the sheltering Pinsapo trees.

The Park’s UNESCO Biosphere status was granted primarily because of the huge stand of the rare Spanish fir, the Pinsapo, here. It only grows in the Sierras Grazalema, Bermeja further south near the coast and Nieve, where we had first discovered it last year. A relic that has survived since before the last ice age it had dwindled to a total of about 700ha but successful conservation and re afforestation programmes have increased its area to over 5000ha.

“Discovered” by Swiss botanist Pierre Boisser in 1837 these prehistoric trees can live from 200 to 500 years so some of these veterans had been here a long time. Sadly climate warming has made them more susceptible to dying from a fungal attack and future planting may need to move to the colder Sierra Nevada and Cazorla.

With a couple of hours till sunset we left the shady heart of the forest and returned to the col passing an ancient snow pit used for centuries to store ice and many trees adorned with large clumps of purple berried mistletoe.

Climbing higher up the switchback road in the morning to the pass of Puerto de las Palomas at over 1300m we stopped at the mirador for breakfast before zig zagging down the northern side weary of the awesome drop close beside us.

The stamped and signed permit allowing us to hike the Sendero La Garganta Verde remained unseen as we started the trail a little later.

The Green Ravine has been slowly carved for millennia by the Bocaleones stream down through the limestone until now, although only 10m wide in places it reaches 400m deep. Sheep grazed unperturbed as we made our way through the thick Mediterranean scrub of broom, wild olive, gorse, mastic, palms and scented herbs. This inner reserve seemed particularly verdant and the plenty full bird life could feast on the heavy crops of fruits and berries.

At a warning sign the path started a steep descent into the gorge, at times on stone steps laid or carved and aided by sturdy handrails. The views below into the depths and above to craggy cliff tops were dramatic.

100 pairs of griffon vultures live above the ravine, the largest colony in Europe, and they constantly took flight from their eyries, riding the thermal updrafts and gliding to and fro on their 8ft wingspans. As we ventured deeper between the towers of rock the air became cooler, more humid, and a silence descended as the breeze was cut off. The Ermita or cave just above the canyon floor revealed itself, clothed in the curious formations of limewater sculpture and the pink and greenish colouration caused by algae action.

Finally reaching the shady still floor thick with oleander, laurel and poplar, our voices bounced back and forth on the canyon walls as we admired the natural stone carving of the Arroyo Bocaleones before starting on the laborious return to the top.

After a night in a room with a view in Zahara de la Sierra overlooking the sadly pretty empty reservoir we returned to the heart of the exclusion zone armed with our final permit- to the Sendero Llanos del Rabel. This easy trail on a wide and smooth forest track goes deep into an area of thick oak forest with views towards the Garganta Verde one way and the El Torreón massif on the other.

We soon came upon one of the many limekilns in the area, used to bake the rock into a powder for spreading on the land and also painting the houses to create the ” pueblo blanco” white villages. All the old holm oaks had multiple branches sprouting from the tops of thick trunks, indicating years of pollarding for fuel. The kilns would have got through a lot of timber.

The variety of trees, particularly of oaks, made for a beautiful tapestry of colour with the holm, gall, portuguese, pyrenean, algerian and even cork (which usually prefers less alkaline conditions) carpeting the mountains in subtle shades of autumn. Some venerable old timers were hollowed and contorted in characterful ways and adorned with lichens and ferns or craggy bark.

Other shrubs and plants were thriving here too. Honeysuckle, clematis, bramble and ivy climbed among the branches. Arbutus, the Strawberry tree dropped its fruit on the track and viburnum berrys hung in clusters.

The track descended to a wide flat area on the valley floor through which a river runs by times and which housed a well placed Finca back in the day. A water trough, old fields and walls and ruined buildings lay silently where a looped trail led us up and around a small hill before we returned to the camper leaving the old homestead to the tree creepers, nuthatches, finches and tits that now made it their home.

That night we moved back toward El Bosque to park up in Benamahoma, next to the river walk that connects the two towns. Although only 4.5km each way we also visited the botanic gardens in El Bosque which made it into a 4 hr hike- the same as the previous three walks. Although this area is renown for high rainfall we had yet to find any running water so the Sendero Rio Majaceite was a swirling, gurgling delight, tumbling down about 150m over the way, past the ruins of several woollen mills. The riverside path occasionally had to cross the rushing water on footbridges or clamber up and down steps to negotiate between cliffs and boulders but was mostly an easy stroll through a lush and shady tunnel.

Emerging onto verdant farmland at El Bosque the benefits of the river waters were obvious in the productive huertas or gardens that lined the bank. There used to be trout raised here in a series of tanks but are now left wild in the river, the most southerly to support them in Europe. They share the waters with otters while dippers, nightingales, warblers and woodpeckers make themselves at home in the thickets of elm, willow and poplar.

The botanic garden was a great place for us to try and get to grips with the names of the Mediterranean plants we have spent so much time walking through. Everything was well laid out and labelled and cared for but with over 300 species of tree it became a bit of factual overload so we stopped to picnic. The return leg along the river was just as pleasant but busier. This is a popular walk and it was a Sunday. I can imagine that the shade and water are a massive draw in the heat of summer.

We drove south through the park toward Ubrique and then up on the switchback A374 to Benaocaz to spend the night amongst a load of other campers on some waste ground. Before the sun set we walked the Sendero Ojo del Moro, to the Eye of the Moor, a look out spot commanding a fine view over the valley of Tavizna. Up a steep rocky path under sheer cliffs we saw the reason for the gathering of campers. This was a popular climbing area and lithe bodies clung to the rock like geckos.

The next days hike was part of a big loop we had planned to do before we found out that some landowner had now closed off the route. But we were able to get as far as the Salto del Cabrero, the Leap of the Goatherd, a geological feature of a big split in the mountain.

It certainly was goat country. The sight of pens and sheds and shelters and the noise of bleating and bells and the smells of billy and shit were all around us as we set off down a path of trampled earth between hoof polished rock.

The wild olive and gorse had been nibbled into glorious topiary by the ever hunger goats and higher up through a sculpture park of limestone boulders and lonely old oaks were grazing long horn cattle.

On the high rocky plateau there was a little cortijo in the distance where we took a spur off the track to a viewpoint of the canyon leapt by the goatherd and watched more vultures patrolling the skies.

Returning the the main track we tried to continue to see the better view of the split from the northern side but soon came upon the closed gates and hostile signage. We didn’t want to blemish our clean record of permit holding, rule obeying conformity and so backed off and retreated from whence we came.

Our final walk was a short exploration from the other end of Benaocaz of the Sendero La Calzada Romana. This route down to Ubrique is on a Roman- Medieval road, parts of which date back to 1st c BC.

Part of a much longer main road from the Med coast to the interior at Córdoba it is impressive in its construction, and durability. Considering it is one of the most popular Senderos in the area and has been trampled by feet, hooves and cart wheels for 2000 years it is doing well.

At an ancient cobbled crossroads it was time to turn back and turn for home.  We’d been meaning to come here for a long time and the Parque had been generous in showing us its splendours. Perhaps we’d been lucky with the weather or perhaps, as the emptying reservoirs and dieing Pinsapo indicated, things were changing. But as the weather worn limestone, Neolithic cave paintings, Roman roads, Moorish castles and abandoned cortijos show,change is a constant, and hopefully the beauty will survive.

We’d been meaning to come here for a long time and the Parque had been generous in showing us its splendours. Perhaps we’d been lucky with the weather or perhaps, as the emptying reservoirs and dieing Pinsapo indicated, things were changing. But as the weather worn limestone, Neolithic cave paintings, Roman roads, Moorish castles and abandoned cortijos show,change is a constant, and hopefully the beauty will survive.

We parked up there overlooking a massive 24/7 olive processing plant, and in the morning left the camper and took the bus back to Granada, found our first arrow, and set off through the suburbs and industrial estates and out onto the industrial farmland beyond.

We parked up there overlooking a massive 24/7 olive processing plant, and in the morning left the camper and took the bus back to Granada, found our first arrow, and set off through the suburbs and industrial estates and out onto the industrial farmland beyond.

A dramatic walking route opened in the Parque Natural de Tejeda, Almijara y Alhama in October 2020 after many months construction. An old path following irrigation canals and pipes into the mountains above Canillas de Aceituno was transformed with a steel and timber suspension footbridge and other hanging walkways fixed to sheer cliff faces.

A dramatic walking route opened in the Parque Natural de Tejeda, Almijara y Alhama in October 2020 after many months construction. An old path following irrigation canals and pipes into the mountains above Canillas de Aceituno was transformed with a steel and timber suspension footbridge and other hanging walkways fixed to sheer cliff faces. The €600,000 investment is hoped to bring in much needed tourist revenue to the area and it seems to be paying off. The day we tackled it the town at the start was busy with people with poles, and the pandemic has led to many more people exploring the vast natural areas away from the more crowded costa. In fact some places such as the Caminito del Rey and El Torcal have become a victim of their own success with long queues, traffic jams and overcrowding but we’ve always found that away from the honey pots Andalucia has space aplenty.

The €600,000 investment is hoped to bring in much needed tourist revenue to the area and it seems to be paying off. The day we tackled it the town at the start was busy with people with poles, and the pandemic has led to many more people exploring the vast natural areas away from the more crowded costa. In fact some places such as the Caminito del Rey and El Torcal have become a victim of their own success with long queues, traffic jams and overcrowding but we’ve always found that away from the honey pots Andalucia has space aplenty.

We’d been meaning to come here for a long time and the Parque had been generous in showing us its splendours. Perhaps we’d been lucky with the weather or perhaps, as the emptying reservoirs and dieing Pinsapo indicated, things were changing. But as the weather worn limestone, Neolithic cave paintings, Roman roads, Moorish castles and abandoned cortijos show,change is a constant, and hopefully the beauty will survive.

We’d been meaning to come here for a long time and the Parque had been generous in showing us its splendours. Perhaps we’d been lucky with the weather or perhaps, as the emptying reservoirs and dieing Pinsapo indicated, things were changing. But as the weather worn limestone, Neolithic cave paintings, Roman roads, Moorish castles and abandoned cortijos show,change is a constant, and hopefully the beauty will survive.

Moving on into the park in the morning we drove up to the Area Recreativa Cuadros and walked through the river side oleander forest that housed many shady picnic tables and benches and up on paths of needles and stone into the pines.

Moving on into the park in the morning we drove up to the Area Recreativa Cuadros and walked through the river side oleander forest that housed many shady picnic tables and benches and up on paths of needles and stone into the pines.

As the winter storm clouds gather over Ireland and the temperature and raindrops fall the call to Spanish adventures cannot be ignored. A 30 hour intermission in a cramped cabin surrounded by a swelling mass of moving ocean and we were once again driving into the mountains heading south.

As the winter storm clouds gather over Ireland and the temperature and raindrops fall the call to Spanish adventures cannot be ignored. A 30 hour intermission in a cramped cabin surrounded by a swelling mass of moving ocean and we were once again driving into the mountains heading south.

Cows and sheep grazing, insects and birds on the ponds and wild growth of heathers, grasses, lichens and mosses all testified to recovery. The paths followed the miles of old railway track, laid down to facilitate the removal of 1000 tonnes of ground a day. 10km of new roads have now been made for phase 2, complete next year and doubling the number of turbines and producing an additional 83MW of clean energy.

Cows and sheep grazing, insects and birds on the ponds and wild growth of heathers, grasses, lichens and mosses all testified to recovery. The paths followed the miles of old railway track, laid down to facilitate the removal of 1000 tonnes of ground a day. 10km of new roads have now been made for phase 2, complete next year and doubling the number of turbines and producing an additional 83MW of clean energy.